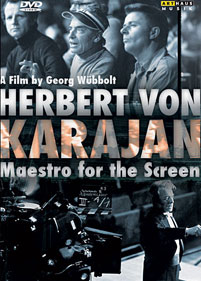

Herbert von Karajan. Un nom qui résonne. Chef, réalisateur, dramaturge et directeur musical, Karajan paraît ici en maître absolu, obsédé par la technologie du son et du visuel. Le réalisateur Georg Wübbolt tente de faire le tour du rapport que le maestro entretenait avec son image. C’est tout l’intérêt. Herbert von Karajan voulait faire plaisir au public du monde en lui faisant découvrir la « grande musique », ce qui lui permettait de faire la promotion de sa propre image. Démagogie ? Sans doute. Cependant, il est un fait indéniable : Herbert von Karajan était un grand chef d’orchestre, vampirisé à la fois par la technique et l’inflation de sa propre image. C’est le paradoxe que ce film retrace fort bien. Malgré sa forme académique d’entretiens à la chaîne (mais comment faire autrement ?), il reste passionnant dans le rapport entretenu par Karajan entre sa folie des grandeurs et sa foi dans la musique. Il serait trop facile de ne le voir que comme un génie de la communication et rien d’autre, comme il serait pénible de ne le considérer que comme un génie interprétatif gagné par l’ivresse des sommets. L’homme, en général, est plus ambigu que cela. Boulimique de la caméra et de sa propre image, esthète perfectionniste et intransigeant, Karajan est évidemment ambigu. Le film de Georg Wübbolt donne la parole aux collaborateurs, aux membres de son équipe technique. Certains tracent son portrait sans flatterie. Narcissique, l'homme à la belle mèche, à la coupe impeccable, possédant jet privé, belle femme et voilier dans le port de Saint-Tropez, est aussi un grand chef d’orchestre. Georg Wübbolt nous montre tous les réalisateurs qui ont travaillé avec lui, tel Henri-Georges Clouzot (le dernier film, le Requiem de Verdi, tourné à la Scala en 1966, est un échec esthétique flagrant), François Reichenbach, Falk, Scholtz, et surtout Hugo Niebeling. Ce dernier démontra que l’on pouvait filmer un concert autrement mais en donnant une forme trop voyante par rapport à la musique (avec de remarquables plans cependant). Herbert von Karajan règnera ensuite seul, contrôlant son image et fondera sa société de production, Telemondial (1982, siège à Monaco). Belle affaire sonnante et trébuchante. Seule fausse note : Karajan crut dans le cd. Une bourde.

Yannick Rolandeau Herbert von Karajan. A name that resonates. Conductor, director, playwright, and musical director, Karajan here appears as an absolute master, obsessed by sound and visual technology. Director Georg Wübbolt tries to examine the mæstro’s relationship to his image, a subject of great interest. Herbert von Karajan aimed to please by allowing the public to discover “great music”, thereby allowing him to promote his own image. Is this demagogy? No doubt about it. Still, there is no denying: Herbert von Karajan was a great conductor, bedeviled both by technique and the inflation of his own image. That is the paradox this film reconstitutes quite well. Despite its academic style of one-after-the-other interviews (but how else can it be presented?), the film sticks passionately to the well-kept relation between his megalomania and his faith in music. It would be too easy to see him only as a genius in communication and no more, just as it would be painful to consider him only as an interpretive genius imbued by the rare air of the mountain tops. In general, the man is more ambiguous than that. Bulimic of the camera and his self-image, and an intransigent, perfectionist esthete, Karajan is clearly ambiguous. Georg Wübbolt’s film allows Karajan’s associates and members of his technical team to speak. Some paint an unflattering portrait. The narcissistic, well-coiffed, well-tailored man, who had a private jet, a beautiful wife and a sailboat in Saint-Tropez, is also a great conductor. Georg Wübbolt shows us all the directors who worked with him, such as Henri-Georges Clouzot (the last film, Verdi’s Requiem, made at la Scala in 1966, is a flagrant esthetic failure), François Reichenbach, Falk, Scholtz, and above all Hugo Niebeling, who demonstrated that there were less ostentatious ways of filming a concert, albeit with remarkable shots. Herbert von Karajan went on to rein alone, controlling his image and founding his production company, Telemondial (1982, headquartered in Monaco). A monetarily convincing business. The only false note is that Karajan believed in the CD. What a blunder. Translation Lawrence Schulman | Disponible sur |  |

|  |